Failing Up

I racked up another big fail this week!

In January, I declared that my word for 2025 is failure.

In March, I nailed a big fail when my manuscript was not acquired by the publishing house with whom I’d been working for ten months.

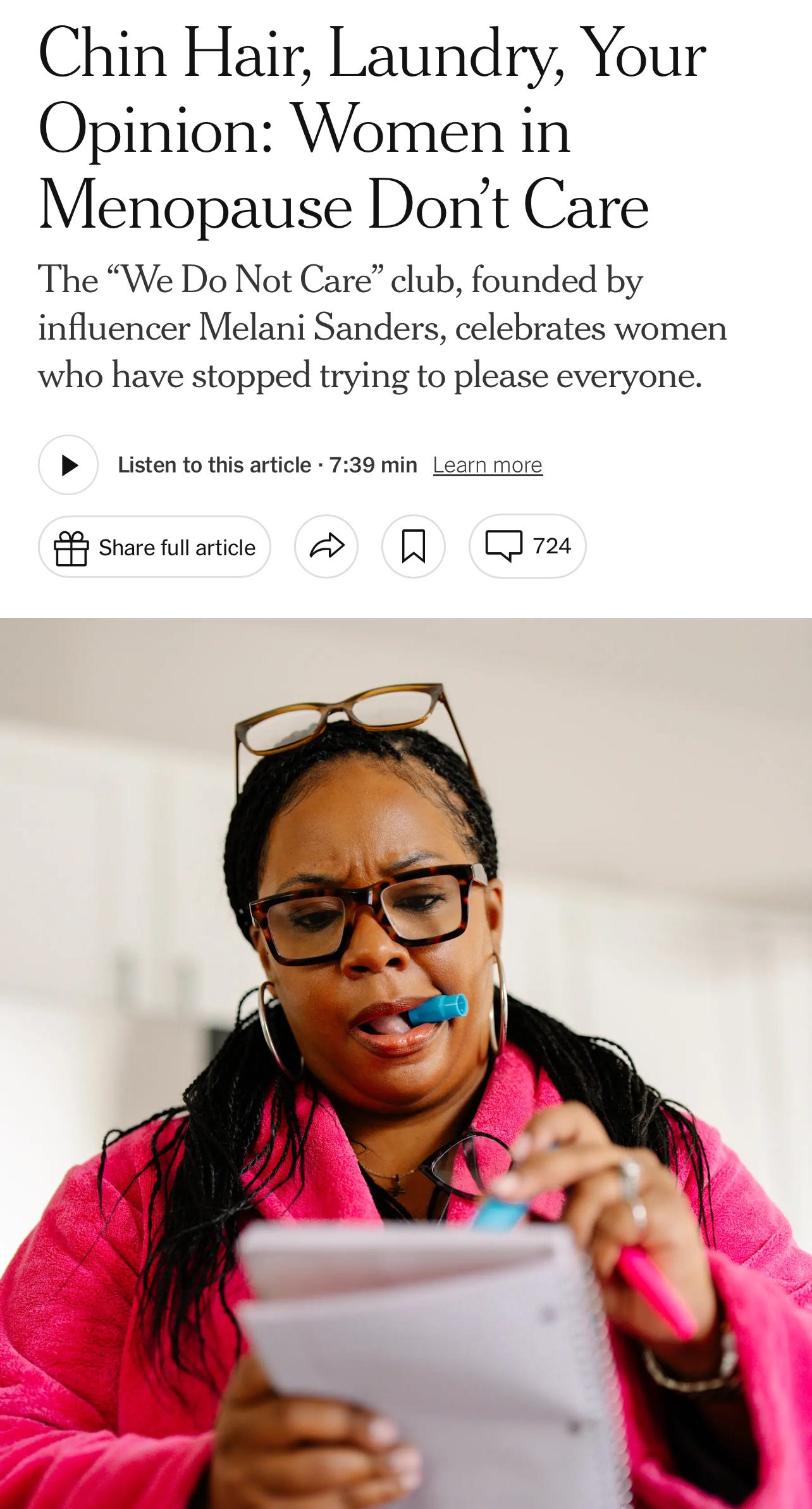

In May, the We Do Not Care Club was launched by the singular force that is Melani Sanders, and millions of us in perimenopause and menopause started the liberating, cathartic work of repackaging our failures into do-not-cares.

In my application video to the WDNC Club, I discussed failing to put on real clothes for school drop-off (“we do not care if we are in the school drop-off line in our pajamas with bedhead wearing slippers and no bra”); failing to wash all the dishes (“we do not care if there are dirty dishes in the sink at night”); and failing to eat a balanced diet (“we do not care if we eat carbs for breakfast, carbs for lunch, carbs for dinner, and carbs for dessert”).

When I teach my strength training classes, I often encourage my clients to fail. Because when we get to that point—when we simply and truly cannot do one more bicep curl with those 15lb dumbbells—that means that our muscles are growing. We are gaining strength.

Failure is the place where the most meaningful growth happens.

I say this in class all the time. It’s become a mantra.

And I needed it this week, because I punched another notch into my belt of 2025 fails, and at first it felt pretty lousy.

On Monday I was interviewed by The New York Times for a profile on Melani Sanders. This was a big opportunity for me. Big. HUGE. The reporter reached out to me because of my WDNC New York chapter videos, one of which went viral, and several others of which are upwards of 50-80K views each. For me to be included in an article about the WDNC Club would be awesome on many levels. It would be an opportunity for me to expand my social media platform, to be publicly acknowledged as a writer, to gain credibility as a voice in the perimenopause space … and it would be simply freaking cool to be able to say I was quoted in The New York Times.

To prep for the article, I reached out to a brilliant friend who runs her own bustling PR business. She helped me come up with three pages of notes and sound bites (thank you, Alyssa!!). I was so, so ready to knock the interview out of the park.

And guess what? I did! I felt great about it. The reporter talked to me for 25 minutes, which is way more time than I thought I would get. I answered her questions about Melani and my WDNC experience, but she also asked me about my personal perimenopause story—which, open book that I am, I loved being able to share. After our interview, I was buzzing. I felt like a badass. And I couldn’t wait for the article to come out.

Even though the reporter said not to expect the article before the end of the week, it was actually out the next day. My mom sent me the link, and my eyes scanned it eagerly for my quote. My moment. My NYT debut.

It wasn’t there. I wasn’t there.

Another rejection. Another gut punch. Another instance of getting my hopes up—She spent 25 minutes talking to me! She said I was very well-spoken! My sound bites were short and punchy!—only to have them dashed.

I saw the article before I saw the reporter’s very kind email letting me know that, due to her editor’s strict word count limit, I was cut. I appreciated that she let me down as easily as she could, but it still hurt.

And that’s the thing: it hurts to fail.

Initially.

It’s how you process the failure, though, that makes the difference.

You can quash the hurt, or deny it (and it will just come back to bite you later).

Or you can feel it.

Feeling hurt is the worst. It sucks. It just does. But then it starts to suck less. Once you recover from that initial gut punch and get your breath back, you create space to process the experience. And that is where the magic happens.

The magic of the mindset shift: from I wasn’t good enough to be in The New York Times to I was interviewed by The New York Times!

I will be the first to admit that it’s not as cool to only be able to say, “I was interviewed by The New York Times” rather than “I was quoted in The New York Times.”

I will be the first to admit that I feel sheepish for telling some friends and family members about the interview and then having to admit I was cut from the article.

But I also know that I will get over it. I will move through this pity party. And then, once I’m fully out of the funk of feeling sorry for myself (I’m almost there now, but not quite, my friends, not quite), I will be able to fully recognize and appreciate that I am failing UP.

My therapist used this phrase the other day, and I latched onto it immediately. Failing up! Isn’t that a beautiful concept? Because my NYT experience may not have turned out as I hoped it would, but I am in a better position than I was before. Because now I have practice being interviewed by a professional reporter. Now I have practice pitching my book. Now I have a contact at The New York Times. And who knows what will happen, or where this will all lead?

Failing hurts. But then it heals. And we are stronger and braver than we were before. Because when we fail, we fail up.

YAAASSSSS! Fail up girl!